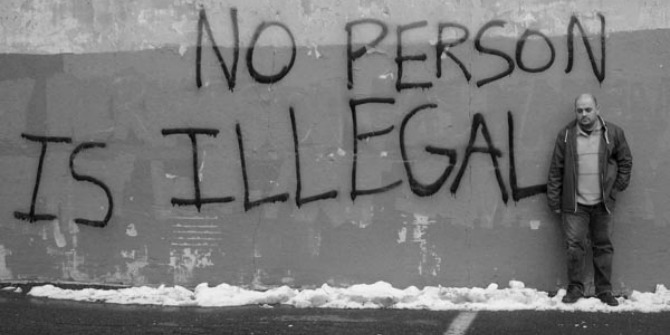

The migration crises in Europe and Southeast Asia has taken far too many lives and continues to create political and social obstacles for the international community to solve. Is violent conflict and political strife the root of the dilemma forcing people to flee their home countries? Or does the problem lie in the way we view those who seek a better life elsewhere?

In a recent New York Times op-ed, the argument was made that referring to these concurrent humanitarian emergencies together as a “migrant crisis” gives license to turn a blind eye to refugees, who have the right to have their applications for asylum considered seriously. The large numbers of Syrians, Somalis, and Eritreans coming to Europe by boat, for example, are likely to be refugees and not simply “migrants,” because of the intense level of armed conflict and political repression in those countries.

“The discussion of numbers, of people-smuggling ‘rackets,’ and of push-and-pull factors,” Ben Doherty wrote in the Guardian, makes the crises in the Mediterranean and Andaman seas an abstract problem instead of a personal one involving human beings. Moreover, Doherty writes, those fleeing on boats – people commonly known as “migrants” – are the silenced voices in the debate.

Meanwhile, the government of Myanmar has continuously refused to use the term “Rohingya” for the 800,000-strong population of ethnic Muslims from western Burma. These people are stateless and in many cases forced into inhumane conditions in camps for displaced people. Most recently, they have been fleeing violence and persecution in their home country and boarding rickety boats headed for refuge in other Southeast Asian countries. By not calling them by their name, Myanmar is avoiding responsibility. Erasing a name from common discourse is a shield from being singled out and forced to offer solutions, which would include an internal and international investigation into the matter.

In fact, government officials from Myanmar had to be convinced to attend a conference in Thailand last week, which addressed cooperative solutions to the crisis. They finally agreed to attend, but only after assurances that the term “irregular migrant” would be used instead of Rohingya.

Semantics takes on another alarming turn when we try to decipher what European leaders really mean when they say their goal is to dismantle the smuggling rings that endanger lives at sea. There is no doubt that smugglers taking financial advantage of desperate situations need to be stopped. But what are the downsides of military operations inside the territorial waters of Libya, the launching pad of many dangerous and ill-equipped voyages? The glaring, obvious con is that innocent people will be killed and their only route out of armed conflict, extreme poverty, and persecution will be destroyed.

Sinking boats allows European countries to postpone making long-term commitments and decisions on refugee and immigration policies while offering a humanitarian guise of assistance. For smugglers, refugees are a commodity. For the EU, asylum-seekers are migrants because European countries can’t afford to let in waves of people.

The European commission this week called on EU countries to take in 40,000 asylum seekers from Italy and Greece. Germany, Sweden, and Austria are in favor of the plan, while the UK, France, and Spain believe that the sharing of refugees should be voluntary not mandatory. For the people caught in between ambiguous labels, the debate is a life or death matter not merely politics.

The international community has criticized Myanmar for refusing to recognize the Rohingya by name, and understating their identity by calling them “irregular migrants.” But in Europe, when leaders point to military action as the only recourse for a human crisis, these refugees are left nameless and stateless, too.

The legal right to seek asylum is just as significant as the historic tendency of humanity to migrate. We are talking about people, not migrants — but the distinction is without a difference.

1 Comment.

[…] insulting. To make matters even more complicated, there is a legal and social difference between the terms refugees and migrants. But in essence, these movers (and shakers) all share at least one thing in common – the quest for […]