Last month, we attended the American Society of International Law (ASIL) 110th Annual Meeting in Washington D.C., where we participated in many conversations about human rights as it relates to mobility in migration. The past year has seen some dramatic shifts in the global economy, the environment, technological innovation, geopolitical power structures, and human mobility.

Migration and refugee law have become central to these structures. And although the Annual Meeting encompassed many different angles of international law, we found the information related to the latest developments in refugee law and global migration most pertinent.

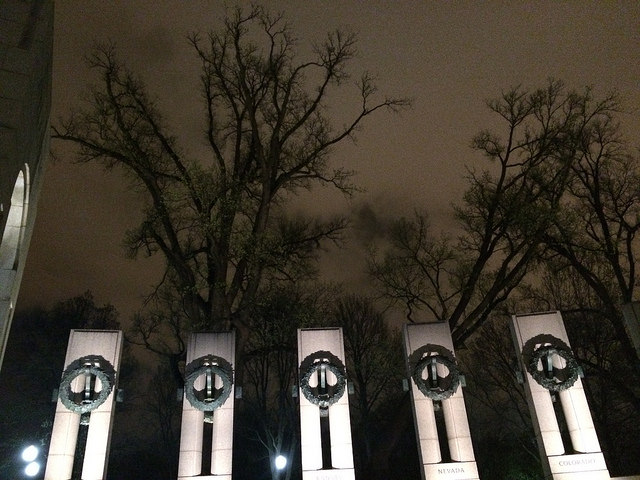

““]

We attended A panel on Migrants at Sea: What Role for International Law, where the responses to Europe’s refugee crisis, at the international, regional, and domestic levels were analyzed. The panel focused on the Mediterranean, primarily, and the different stages of a migrant’s journey. Most enlightening were discussions on what rights refugees have to seek asylum in certain EU countries and what kind of protection is afforded at sea – there is an obligation to assist. However, once migrants and refugees arrive in Greece, for example, there is no general right to move further and no requirement to let people travel to other countries or to protect them as their journey continues.

General refugee protection policies were also analyzed, including those in Jordan, Turkey, Lebanon, Greece, and Germany. Across the board, there seems to be a major failure on the part of all countries (host, transit, and receiving) in protecting unaccompanied minors, mostly from Afghanistan and a significant number of Syrians. This observation begs a comparison about the treatment of unaccompanied minors in Europe to Central American minors in the U.S. (we’re working on it).

According to the panelists, Europe need to focus on two key priorities in order to most effectively handle the current migrant crisis. First and foremost, the EU must help Greece with reception capacity; and secondly, Europe must provide more support to Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon. Because most refugees want to return back home when it is safe, they choose to stay in “frontline” countries, or countries from which they can easily depart to return back home. Europe should help to improve their living conditions in these temporary homes. The final recommended priority was the dismantling of smuggling rings and trafficking networks, since “businessmen” are profiting from people’s suffering.

The panelists also made clear their commitment to semantics. According to them, what is happening in Europe is a refugee problem, not a migration one. As we see it, migration in all its forms, regardless of push and pull factors, is a human rights issue and quickly becoming the human rights issue of our time.

The academics and policy analysts of the International Migration Law Panel are pioneers trying to create more space for this long overdue discussion on migration in the arena of international cooperation. Historically, decisions about the admissions of migrants onto a state’s territory has been viewed as largely within the authority of individual states. Because of this, there has been no focal point for advancing academic conceptualization of migration law and its application to pressing challenges posed by the growing transboundary movement. But the current international law affecting migration leads to gaps and contributes to the migration crisis. The field is under-theorized and often focuses on the arbitrary difference between political refugees and economic migrants. Since disorder affects both categories of people equally, stressing on this international law distinction is often time-consuming and pointless.

What’s missing from international law as it governs migration is a multilateral approach. We’ve heard former UNHCR head Antonio Gutterres say this many times – we can’t just have a set of international norms governing refugees; there is a growing need for a system formalizing migration more generally.

A question that wasn’t answered but will continue to float around for some time to come: Is there a need for another UN convention addressing migration as a whole?

“This is a long overdue conversation,” said Janie Chuang of the American University of Washington College of Law. The role of remittances and Internally Displaced People (IDPs) and how they fit within a future regime or field of international migration law was also analyzed.

At the moment, it seems as though human rights does not encompass migrant rights, at least not as much as it should. But the idea is gaining some momentum. As immigration advocates, we hope to give this conceptualization more public recognition.