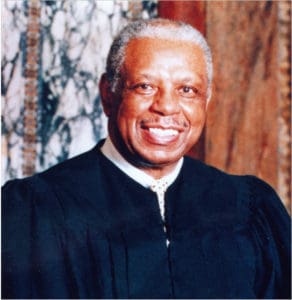

Last Sunday, Federal Judge, Civil Rights icon, and Detroit native Damon Keith passed away at the age of 96. Throughout his long and prolific career, his judicial opinions touched everything from housing segregation to school integration. Yet, it was his efforts to keep the U.S. Immigration Court system just and transparent that remain some of his most influential. Specifically, his decision on the 2002 Sixth Circuit Court case Detroit Free Press v. Ashcroft which as the New York Times described “yielded one of Keith’s most memorable opinions.”

To understand the significance of this decision, it is important to know the historical context under which it came about. It was 2002 and the United States was still reeling from the 9/11 terrorist attacks that had occurred not even a year prior. In response to the attacks, the Federal Government crafted multiple (now infamous) policies that limited government transparency and individual freedom in the name of national security. One of these policies restricted who could attend the deportation hearings of foreign aliens.

Under the direction of Attorney General John Ashcroft, the Chief Immigration Judge, Michael Creppy, instructed immigration judges to close to the public and press all immigration hearings thought to be of “special interest” to the September 11 investigation. In what came to be known as the “Creppy Directive,” the rule defined special interest cases as “those where the alien is suspected of having connections to, or information about, terrorist organizations that are plotting against the United States.” These cases were intended to be handled in secret and closed off from the public in order to uphold a “compelling government interest” of national security. Officials would close the cases to any public or press and remove them from the court’s docket, eliminating the cases’ public record.

This brings us to Detroit Free Press v. Ashcroft. On December 14, 2001, Rabih Haddad, a Lebanese national, was arrested after his temporary visa expired. This in of itself was not unusual. However, Haddad had been operating an Islamic charity that was suspected of funneling assets to a terrorist organization causing the government to label his case as special interest. Following this classification, immigration officials detained Haddad, denied him bail, and had his case closed from the public and press. Believing this closure to be a violation of their First Amendment rights to speech and press, The Detroit News, Detroit Free Press, Metro Times, Haddad, and Michigan Representative John Conyers filed suit against the Federal Government claiming that the Creppy Directive was unconstitutional.

After a victory for the plaintiffs in the lower district court, Keith and the other Sixth Circuit Court judges unanimously affirmed the ruling that the blanket use of the Creppy Directive was unconstitutional. The court held that in order to prevent the disclosure of information in immigration hearings, it must have a “compelling government interest, and [be] narrowly tailored to serve that interest.”

It found that although the Haddad trial did have a compelling government interest of national security, it was not narrowly tailored since the government could apply the “special interest” label to virtually any immigration hearing it wanted. Therefore, the court ruled that it could not apply the Creppy Directive, and label this case a special interest one in order to close it to the public and press.

In spite of this legal victory, the triumph was short lived as other circuit courts issued conflicting rulings on similar cases and secret immigration proceedings would continue on for years. Yet, it was this case that generated one of Keith’s most memorable opinions and of one of his most signature quotes, “democracy dies behind closed doors” exemplifying his strong belief in transparency and fairness in the country’s justice system regardless of a person’s immigration status. A lesson that is still very much applicable in the present where our administration shamelessly pursues ways to undermine the due process of undocumented immigrant, asylum seekers, and others currently making their way through this country’s immigration courts.