Of all the immigrant groups that sought out opportunities in the United States, one of the largest demographics, Irish immigrants, saw an estimated influx of almost 4.5 million – including my ancestors – between 1820 and 1930. Their migration was fueled by the potato famine that ravaged the island in the mid-1800s as well as the inequitable socioeconomic system furthered by wealthy British rulers.

In fact, the civil servant tasked with heading relief efforts for the potato famine said, “The judgment of God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson, that calamity must not be too much mitigated”. For what exactly were they teaching the Irish a lesson? Mostly for practicing Catholicism, in addition to wanting to speak their own language and owning their own property. As a result, many took to over-packed ships in the hopes of reaching the United States. Unfortunately, half of those who set sail would not make landfall and instead their bodies were tossed overboard – rampant hunger and disease, exacerbated by outrageously cramped quarters, made survival difficult during the voyage.

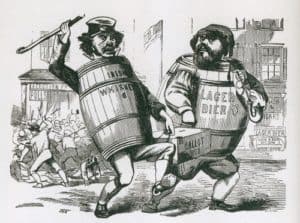

Bias against Irish immigrants already existed long before the mass exodus, yet another result of Catholic – Protestant tensions fueled by generations of previous Anglo-Saxon Protestant immigrants living in the United States. The Irish took labor-intensive, low pay jobs such as digging trenches, laying railroads, blacksmithing and house cleaning. Some even sided with Mexico during the Mexican-American war as a result of mistreatment by the Americans. These Irish immigrants were deemed traitors by the U.S. government and were subsequently executed. Furthermore, the Roman Catholic Irish population was scapegoated and falsly blamed for straining social services, causing politicians to lose elections (such as Fillmore’s 1844 defeat) and other offenses against the United States . In the most egregious circumstances, their churches were burned, those of Irish descent were murdered in the streets as well as barred from voting and targeted by various nationalist groups. A 2016 article from The Boston Globe describes how the Irish were represented in popular media at the time:

“In the popular press, the Irish were depicted as subhuman. They were carriers of disease. They were drawn as lazy, clannish, unclean, drunken brawlers who wallowed in crime and bred like rats. Most disturbingly, the Irish were Roman Catholics coming to an overwhelmingly Protestant nation and their devotion to the pope made their allegiance to the United States suspect.”

So how is it that the Irish managed to navigate up from the lowest rung of society? By doling out the same racist and nativist rhetoric that had kept the previous generation suppressed and marginalized. The Irish, once considered to be the lowest group on the American social ladder, used racist leverage against other nationalities to separate themselves and elevate their societal status. Their vitriol was directed towards those who occupied lower rungs on the societal ladder: African-Americans and slaves, the Chinese and Eastern European immigrants.

There is a popular historical myth that implies that the Irish were also brought to the U.S. as slaves and were treated similarly as African slaves. This argument is largely used to discredit the negative effects of slavery and remove the onus from white Anglo-Saxon Protestants as those who made these atrocities happen. This is an entirely false argument. While minuscule amounts of Irish individuals were subject to forced labor, their experiences pale in comparison to the horrific atrocities experienced by African slaves long before and during that same time period. This myth that has been warped into a popular argument against slavery stems from rampant misinformation. The original historical facts have been blown out of proportion and are now used to challenge one of the darkest periods of American history. The Irish were clearly targets of bias, but as part of the larger narrative of bias and othering in American history, they did not suffer the long-term societal effects that those of other populations do. This is why Irish immigrants and their descendants have assimilated into American society, from which the United States has undoubtedly benefited.

My own personal ancestral story involves the first maternal relative of mine to immigrate to the United States. His name was James and unlike most Irish immigrants who came to the U.S. fleeing famine, he immigrated to escape the Irish Republican Army (IRA). James was on an IRA hit list and fled Ireland for Canada to evade his imminent death. He later entered illegally through the porous Canadian border into Montana, where he worked in the copper mines until he could afford a move to Detroit.

Once James was established in the United States, other relatives began to arrive. My great-grandparents were Irish immigrants whose names can be found at Ellis Island. My great-grandfather immigrated from Ireland in 1915 aboard the St. Louis and my great-grandmother immigrated in 1930 aboard the Mauretainia. They met here in the United States and after fighting for the Allies in World War I, my great-grandfather took a job in construction in Detroit.

It was there that they met and began to exchange correspondences – one of their five children is my grandmother, who recounted our family history to me. They were fortunate to have been born long after the potato famine and a time when Irish immigrants were viewed as undesirables. As our family grew, they stayed close – living in the same Detroit neighborhoods, helping each other find work, and raising their children together. To this day, all of us still live in Detroit and the metro area having contributed to and been a part of one of the largest immigrant demographics that has enriched and diversified the fabric of Michigan as a state and the U.S. as a whole.

Further reading: